One minute your dog is fine, and the next they are staggering with their head listing to one side. It looks like the canine equivalent of a human stroke. What’s going on? While it could be a stroke or other serious condition, in a gray-muzzled dog, it’s often idiopathic vestibular disease, more commonly known as what’s called old-dog syndrome. And that’s actually good news.

Feeling Dizzy

Located in the inner ear and brain, the vestibular system helps dogs maintain balance and coordinate the position of the head, eyes and legs. Anything that disrupts this system can throw your dog’s balance out of whack. And in older canines, it’s not rare that this happens. This syndrome is considered to be “idiopathic,” meaning that no one knows, exactly, what causes it. While old-dog vestibular syndrome generally affects older dogs, it can occur in cats of any age.

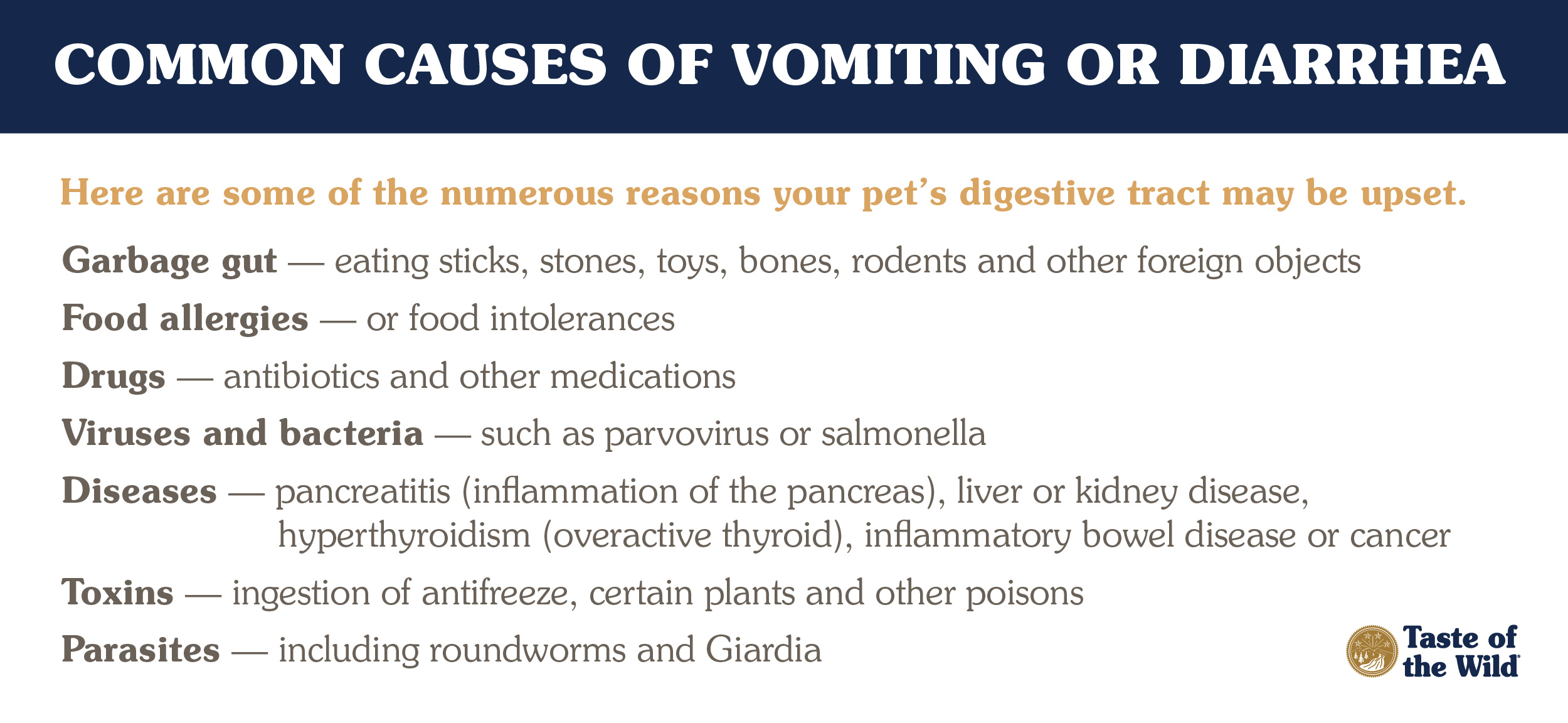

You’ll know it when you see a sudden head tilt, loss of balance, falling or rolling to one side, circling, trouble walking and abnormal eye movement, often from side to side. As you can imagine, these symptoms are often accompanied by dizziness, nausea, vomiting and loss of appetite.

Although these signs can be frightening, the good news is that most dogs recover from vestibular disease. While some retain a head tilt, they seem to regain their sense of balance and do just fine.

Strokes Can Have Similar Signs

Like humans, dogs can have strokes, but they typically aren’t as common as in people. Strokes can be caused by the rupture of blood vessels or blocked arteries in the brain. They can also be caused by fibrocartilaginous emboli (FCE), or material that travels through the blood and lodges in a blood vessel, often in the spinal cord.

Like vestibular syndrome, a stroke or FCE can occur suddenly. With the latter, especially, a dog may leap after a tennis ball, yelp with pain and immediately have difficulty walking. This can occur in dogs of all ages. Signs of a stroke can be subtle but may also include head tilt, circling, weakness, paralysis of one or more limbs, loss of urine or bowel control and collapse.

To complicate matters, other conditions can cause signs similar to old-dog vestibular syndrome, including inner ear infections, hypothyroidism (low thyroid hormone), toxins, trauma, infectious diseases or brain tumors.

Pinpointing a Cause

Because these signs can indicate a potentially serious disease, it’s important to see your veterinarian as soon as possible. The doctor will perform a full physical exam, including looking for signs of inner ear infections and neurological problems. In addition to possible blood or urine tests, your veterinarian may recommend X-rays to help visualize the middle and inner ear, which can’t be seen on physical exam.

A Wait-and-See Approach

In many cases, the veterinarian may monitor older dogs before performing more tests. While the signs can be severe for 48 to 72 hours, those with old-dog vestibular syndrome often improve gradually over the next few days to weeks.

Dogs that don’t show signs of improvement in a few days typically require additional diagnostics, which may include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) for evidence of a stroke or other brain lesions.

Your veterinarian may prescribe medications to help reduce motion sickness. It may also help to hospitalize the dog, or limit them to an area of the house with soft carpeting and no stairs to help minimize possible injuries from falls. With prompt veterinary attention, most dogs with old-dog vestibular syndrome — and strokes — eventually recover.